Volume 12 - Year 2025 - Pages 69-78

DOI: 10.11159/jbeb.2025.009

Unique Trends in Methadone Adverse Event Reporting During Health Emergencies

Nysa Anand1

1Normal Community High School

3 Callahan Ct, Bloomington, United States 61705

nysaanand19@gmail.com

Abstract - The objective of this study was to examine the trends in adverse event reporting for methadone before, during, and after global health emergencies. This study highlights the most recent global health emergency of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study utilized the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System to analyze methadone adverse event reports and compare these trends with those of all medications. The study finds that 18.8% of all methadone-related adverse event reporting occurred in 2021, with 21,257 out of 22,447 adverse event cases classified as serious adverse events, and 10,109 resulting in death. There was a 320.9% increase in reported adverse events for methadone between 2012 and 2013, marking the first major uptick in methadone adverse event reports. Overall, there was a 1297% increase in reported adverse events for methadone across the decade of 2011 to 2021. The trend in adverse event reporting for methadone did not match the trend in adverse event reporting across all medicines. There was a 61.9% increase in reported adverse events for methadone between 2020 and 2021, while the increase in reported adverse events across all medicines was only 5.7% over this same period. The study additionally finds that 51.2% of reported cases for methadone adverse events were from men. Additionally, the greatest proportion of reported adverse events for methadone involved drug dependence, making up 21.8% of all reported adverse events for methadone. The results highlight that increases in reported adverse events for methadone during the COVID-19 pandemic are unique to methadone, and cannot be attributed to a general increase in reporting of adverse events across all pharmaceuticals. This indicates that opioids used to treat OUD are at risk for higher misuse during emergencies. Further research could examine trends in adverse event reporting in other substances used to treat opioid use disorder, and potential solutions to counteract increased opioid usage in times of widespread infectious disease.

Keywords: adverse events, COVID-19 pandemic, methadone, opioid use disorder

© Copyright 2025 Authors This is an Open Access article published under the Creative Commons Attribution License terms. Unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Date Received: 2025-04-04

Date Revised: 2025-09-02

Date Accepted: 2025-10-14

Date Published: 2025-11-25

1. Introduction

Opioids have been used to manage acute, terminal, and chronic pain from the earliest human times. In 3400 B.C., the euphoric effects of the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) were recognized under the term “joy plant” [1]. Ancient Greece utilized the characteristics of this plant in the 8th century B.C., describing preparations of sedatives and hypnotics [2]. Later, opium was recorded to be held over the nose as a form of painkiller during the earliest forms of Western surgery [1]. More recently, however, opioid usage has developed some increasingly concerning consequences. Nearly 727,000 deaths in the United States were caused by opioid overdoses between 1999-2022 [3]. On October 16th, 2017, the United States Government declared the opioid epidemic a public health emergency under section 319 of the Public Health Service Act, and this declaration was most recently renewed in June 2024 [4].

1. 1. The Opioid Epidemic

Today’s opioid epidemic is characterized by a spike in overdose deaths related to the misuse of prescription and illegal opioids and has impacted the United States immensely. The use of opioids has increased by approximately 10 times over the 20-year period from 1997 to 2017 [5]. Deaths by opioids continue to rise; an estimated 224 people died daily in the United States from opioid overdose in 2022 [3].

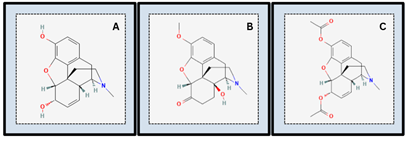

Opioids are a class of natural, semi-synthetic, and synthetic drugs, such as heroin, oxycodone, methadone, morphine, and fentanyl (Figure 1), which are defined as medications that bind to opioid receptors [6]. In signaling pathways, opioid receptors function as painkillers, inhibiting the transmission of pain neurotransmitters and inducing analgesia [2]. However, the involvement of opioids in long-term treatment plans has become increasingly controversial. As these medications have become more accessible in pain treatment, opioid addiction and abuse have become more frequent. The surge in opioid usage can partially be attributed to commercial marketing strategies to physicians who prescribe these products.

Morphine (Figure 1A) is a non-synthetic narcotic and is utilized as a painkiller [7]. Originating in the United States and derived from opium, morphine induces euphoric feelings that lead to tolerance and dependence, resulting in a high potential for abuse [7]. Oxycodone (Figure 1B) is a semi-synthetic narcotic that induces feelings of relaxation and serves as an analgesic for pain relief [8]. Oxycodone is primarily marketed through OxyContin, and the product is legal under Schedule II of the Controlled Substances Act, meaning that although it is currently accepted for medical use in the United States, it has a high potential for abuse and may lead to severe physical or psychological dependence [8]. Euphoria is the most common effect of oxycodone usage, hence the opioid has a high addictive potential for abuse [8]. Heroin (Figure 1C) is an illegal semi-synthetic opioid derived from morphine that induces euphoria [9]. Heroin is extremely addictive and is classified as a Schedule I drug, meaning that it has no safe, accepted medical use in the United States due to its high abuse potential [9]. Fentanyl, (Figure 1D), is a synthetic opioid analgesic and a highly addictive drug [10]. Fentanyl is approximately 100 times more potent than morphine and approximately 50 times more potent than heroin [10]. A fentanyl dosage as small as 0.25 mg is considered a potentially lethal dose [10]. Due to fentanyl’s high potency, it is much more deadly, and transdermal fentanyl can kill [11]. Unlike heroin, fentanyl has FDA-approved commercial medical use for post-surgery chronic pain [10]. Fentanyl also induces euphoric effects similar to other commonly used opioids, such as morphine [10]. Methadone, (Figure 1E), is a synthetic opioid that is primarily used in treating opioid use disorder and managing chronic pain [12]. Methadone’s unique characteristics, such as its lipophilic nature and long half-life, contribute to its high potency and long-lasting effects on opioid receptors and signal transduction pathways [12].

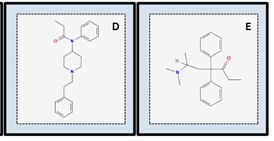

The opioid epidemic can be categorized into three distinct waves of opioid overdose deaths (Figure 2), based on trends in overdose deaths from any opioid, synthetic opioids, commonly prescribed opioids, and heroin. The first wave of the opioid epidemic began in the 1990s. This period is characterized by an increased prescribing of opioids, and the primary cause of overdose deaths was commonly prescribed opioids, involving natural opioids, semi-synthetic opioids, and methadone. Oxycodone was one of the opioids prevalent during the first wave of the epidemic, and it served as a gateway to illicit drug use and a spike in heroin use [13]. While most drug users initially started with Oxycodone pills, they transitioned to nasal inhalation and injections for heroin usage, which essentially progressed to the second wave of the opioid epidemic [13]. The second wave of the opioid epidemic began in 2010 and was characterized by an increase in heroin deaths. Overdose deaths by commonly prescribed opioids had begun to stabilize, but stayed high. The third wave of the opioid epidemic began in 2013 and was characterized by an increase in overdose deaths by synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl and tramadol. Overdose deaths by commonly prescribed opioids continued to stay relatively consistent during the third wave. Heroin usage had decreased during this third wave, but overall opioid overdose deaths had multiplied by approximately nine-fold as compared to 1999 [3].

When an individual takes a higher dosage of an opioid than their body can handle, an opioid overdose occurs [6]. Opioid overdose can induce deadly symptoms [6]. These symptoms include unconsciousness, difficulty breathing, discolored skin, nails, or lips, and constricted pupils [6]. An overdose can be intentional or unintentional, and it usually results from multiple drugs being mixed [6]. For example, overdose deaths in adolescents have been on the rise due to lethal doses of fentanyl being mixed into counterfeit pills as well [6].

In 1995, OxyContin, an oxycodone-based narcotic painkiller, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [14]. Shortly after, in 1996, Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin to the market, available only by prescription [14]. Purdue Pharma aggressively marketed OxyContin, spending 6 to 12 times more on promoting the product than competing pharmaceutical manufacturers, and sales of this product grew from $48 million in 1996 to nearly $1.1 billion in 2000 [14]. One of the primary marketing strategies used involved unethical business practices: misrepresenting the risk of addiction to OxyContin [14]. Purdue Pharma claimed that the risk of addiction to OxyContin was extremely small, stating that the risk of addiction was “less than one percent”, and supported this claim with data from clinical studies that focused on populations with acute pain and short-term usage of the product [14]. Purdue Pharma’s data did not accurately account for long-term OxyContin usage and patients who were facing chronic pain, thus misleading the public on the true effects of their product [14]. By marketing and promoting the use of OxyContin in this way, Purdue Pharma demonstrated that pharmaceutical marketing strategies can play a major role in drug misuse and the opioid epidemic as a whole.

1. 2. Opioid Usage

Despite being intended as a treatment for chronic non-cancer pain, opioid usage has many common side effects, the most prominent being constipation and nausea [1]. Other common side effects include sedation, dizziness, vomiting, physical dependence, and respiratory depression [1]. When an individual takes a higher dosage of an opioid than their body can handle, an opioid overdose occurs [6]. Opioid overdose can induce deadly symptoms [6]. These symptoms include unconsciousness, difficulty breathing, discolored skin, nails, or lips, and constricted pupils [6]. An overdose can be intentional or unintentional, and it usually results from multiple drugs being mixed [6]. For example, overdose deaths in adolescents have been on the rise due to lethal doses of fentanyl being mixed into counterfeit pills [6]. Additionally, prolonged usage of opioids has some adverse consequences, including tolerance, hyperalgesia, hormonal effects, and immunosuppression [1]. Prolonged opioid usage leads to a loss of analgesic potency, meaning that the dosage must continually increase to achieve the same level of effectiveness as time goes on, inducing a dependency on opioids [1].

Aside from tolerance, another primary cause of dependency on opioids lies in opioid receptor structures and receptor signaling cascades [2]. In conventional opioid receptor signaling, the primary opioid receptors are mu (MOR), delta (DOR), kappa (KOR), and nociceptive (NOPR) opioid receptors [2]. In these signaling pathways, when opioids bind to mu-opioid receptors, they create a signal in the brain’s ventral tegmental area (VTA), triggering a release of dopamine, which induces euphoric feelings of pleasure [15]. Repeated use of opioids causes the brain to associate these feelings with taking the opioid, leading to opioid cravings and, in most cases, addiction [15].

1. 3. Opioid Signaling Pathways

To understand the impact of opioids, it is critical to examine the basics of conventional pain-signaling pathways [12]. Pain transmission begins with detecting chemical, thermal, or mechanical stimuli that trigger serotonin and norepinephrine release. These signals are then sent back down via the locus coeruleus and nucleus raphe magnus to help reduce pain at its source [12]. Serotonin release activates opioid-releasing neurons to block pain, and norepinephrine release triggers receptors in the spinal cord to aid in reducing pain [12]. Meanwhile, glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors serve to transmit and amplify pain signals, respectively [12]. Repeated release of these pain signals over-activates these receptors, leading to long-term, chronic pain [12].

Transduction processes of conventional opioid receptor signaling rely on G protein-coupled receptor-transducer (GPCR) interactions, which decrease the level of cellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), which hinders the effects of the cAMP signaling cascade [2]. As a result of the reduced cAMP production, reduced presynaptic release of neurotransmitters inhibits the transmission of pain signals throughout the body, hence causing analgesia [2].

1.4. Methadone as an Opioid

Methadone is a long-term opioid agonist that is most well-known for its role in opioid maintenance therapy and treatment [12]. It is an analgesic for acute and chronic pain management [12]. Its longer half-life in comparison to most clinically used opioids as well as its ability to attach to mu, delta, and kappa opioid receptors, make it an effective opioid agonist [12].

Methadone is a synthetic, easily manufacturable, and cost-effective substance that has unique pharmacological properties, enabling it to differentiate itself from mainstream opioids such as fentanyl and morphine [12]. One property includes high lipid solubility, which leads to increased bioavailability and prolonged impact [12]. After repeated administration, methadone still has an analgesic effect after 8-12 hours and inhibits serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake in the central nervous system [12]. Additionally, methadone has many routes of administration, such as buccal, topical, neuraxial, and intravenous routes, and can be administered most effectively through oral or nasal pathways [12].

In methadone signaling pathways, the opioid agonist binds to mu-opioid receptors (Figure 3), resulting in signaling transduction and cascades very similar to those of conventional opioids, reducing the presynaptic release of neurotransmitters, and inhibiting the transmission of pain signals, and causing analgesia [12].

However, methadone inhibits serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake as well, enabling the neurotransmitters to continue to block and reduce pain by sending further messages between nearby cells rather than being absorbed by a presynaptic nerve [12]. Additionally, methadone blocks the NMDA and glutamate receptors, reducing the transmission and amplification of pain signals, and it prevents the nervous system from being overstimulated by pain, reducing the risk of hyperalgesia and chronic pain [12]. These collective factors enable methadone to be an extremely effective analgesic, especially in opioid-tolerant patients [12].

As an opioid agonist, methadone has many adverse consequences that are similar to those of standard opioids, including respiratory depression, euphoria, nausea, sedation, miosis, physical dependence, and tolerance [12]. Methadone is a strong central nervous system (CNS) depressant, and when combined with other CNS depressants, such as alcohol, it can cause significant negative CNS effects [12]. Methadone is also a federally designated Schedule II drug [12]. Since methadone has a steady plasma concentration, it does not offer pleasurable sensations and the typical drug craving associated with standard opioids like heroin, morphine, and oxycodone [12]. However, it does create strong sedative effects that can lead to euphoric feelings [12].

As with the long-term use of all agonists, methadone has a high chance of resulting in physical dependence [12]. Physical dependence is a term used to refer to changes in the nervous system's function caused by prolonged opioid binding to receptors, leading to receptor-mediated adaptations over time [12]. These changes can cause the body to rely on the drug to function normally, and stopping or reducing drug usage results in withdrawal symptoms, such as anxiety, agitation, restlessness, hyperhidrosis, and tachycardia [12]. Additionally, after chronic exposure to opiates, the MOR receptors become desensitized to the methadone binding, leading to tolerance [12]. Because of this occurrence, over long-term periods, methadone intake leads to a decreased drug response in the body, requiring an increase in dosage to achieve an effective analgesic effect [12].

Because methadone has been seen to be an effective analgesic and plays a critical role in opioid maintenance, it is crucial to understand the impact of the pharmacological adverse effects and consequences of methadone usage. The objective of this research is to investigate reported adverse events for methadone and trends in adverse event reports in the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic eras, focusing on the impact of COVID-19, sex, and age, to identify patterns that could inform clinical practice and public health surveillance.

2. Methods

This study aims to investigate and perform an analysis of reported adverse events for methadone and trends in adverse event reports in the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic eras by employing a combination of statistical analysis and data extraction from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Public Dashboard. The pre-pandemic era is defined as the period from 2011 to 2019. The pandemic era is defined as the period from 2020 to 2021, with peak pandemic conditions in 2021. The post-pandemic era is defined as the period beginning in 2022 and beyond.

The FAERS is a web-based platform that allows the general public to access data reported to the FDA on human adverse events associated with pharmaceuticals. The FAERS Public Dashboard contains all reports of adverse events from ICBB 139-4 both mandatory reporters (pharmaceutical manufacturers) and voluntary reporters (healthcare professionals and consumers) for all medicines approved for use in the United States. The FAERS public dashboard was searched using the term “methadone”, and data on case count by received year, serious cases including death, case count by reaction, and case count by sex were collected. A serious adverse event is defined by the FAERS Public System as one that is life-threatening or that requires hospitalization.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Trends

Methadone has had FDA approval for the treatment of opioid addiction since 1972, but adverse events reported for methadone began to increase substantially in 2013 (Figure 4). Between 2012 and 2013, the first major increase in reported adverse events for methadone occurred, with a percent increase of 320.9%.

There were a total of 2,606 adverse event reports for methadone in 2020 and a 61.9% increase in methadone adverse event reports between 2020 and 2021. There was a spike in adverse event reports for methadone in 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a total of 4,219 cases reported that year. There were a total of 2,259 adverse event reports for methadone in 2022, a 46.5% decrease in methadone adverse event reports between 2021 and 2022. Overall, there was a 1297% increase in reported adverse events over the decade from 2011 to 2021.

The trend in reported adverse events for methadone from 1998 to 2024 does not match the overall trend for reported adverse events for all pharmaceuticals collectively in the FAERS database (Figure 5), meaning that methadone exhibited unique increases in reported adverse events over this timeframe. The 320.9% increase in reported adverse events for methadone from 2012 to 2013 is specific to this medication; by comparison, the increase in reported adverse events for all medicines from 2012 to 2013 was 14.9%. The 61.9% increase in reported adverse events for methadone from 2020 to 2021 is also specific to this medication; by comparison, the increase in reported adverse events for all medicines from 2020 to 2021 was 5.7%. While the number of reported adverse events for all medications steadily increased over the decade from 2011 to 2021, the increase was not nearly as dramatic as that for methadone. While methadone demonstrated a 1297% increase in reported adverse events from 2011 to 2021, all medications together demonstrated a 197% increase in reported adverse events over the same time period. There was no clear spike in total reported adverse events for all medications during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.2. Serious Adverse Events

The FAERS Public System indicates that 18.8% of all methadone-related adverse event reports occurred in 2021. Additionally, of the 22,447 adverse event cases reported for methadone over all years, 21,257 were classified as serious adverse events. This means that 94.6% of all reported adverse events for methadone are serious adverse events (this includes death). Of the 22,447 adverse event cases reported for methadone over all years, 10,109 resulted in death. This means that 45.0% of all reported adverse events for methadone resulted in death.

3.3. Demographic Trends

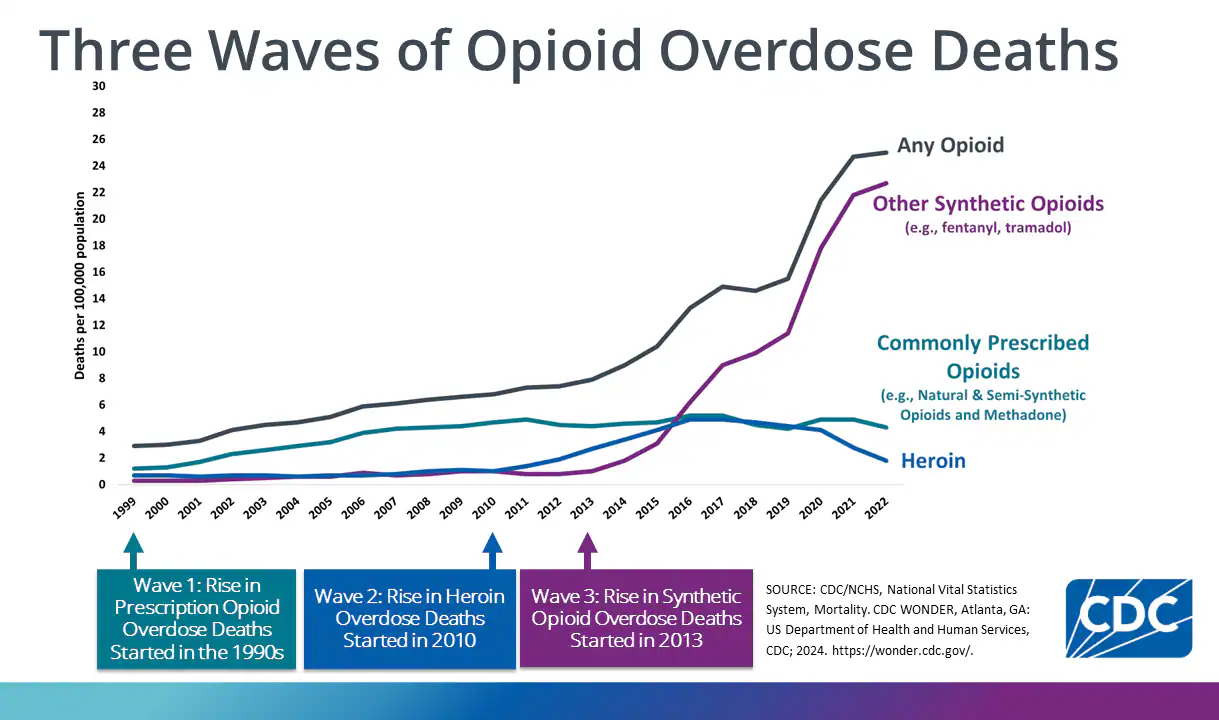

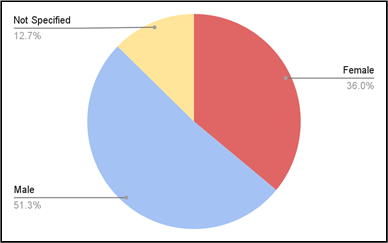

Notably, when adverse events are classified by sex, men account for a greater proportion of reported adverse events for methadone than women (Figure 6).

Men make up 51.21% of reported adverse event cases, and women make up 36.08% of reported adverse event cases. The remaining 12.71% of adverse event reports did not specify the sex of the individual. This differs from total adverse reports across all medications, in which women made up 53.22% of reported adverse event cases. For both reports for methadone and across all medications, the age range of 18-64 years makes up the greatest proportion of cases. However, the majority of methadone reports come from this demographic: 53.43% of reported cases for methadone come from individuals between 18-64 years of age, while only 35.12% of reported cases across all medications come from this age range.

3.4. Reaction-Type Trends

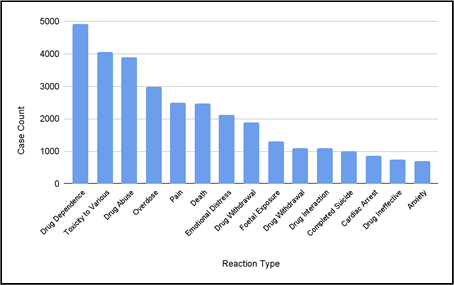

When adverse events are classified by reaction type, the greatest proportion of reported adverse events for methadone, 21.8%, involved drug dependence (Figure 7). Toxicity to various agents, drug abuse, and overdose were also frequently reported adverse events for methadone.

4. Discussion

The results of the study highlight that the increases in reported adverse events for methadone in 2013 and 2021 cannot be attributed to an overall increase in reporting of adverse events for all pharmaceuticals. In 2021, the number of reported adverse events for methadone was 14 times the number of reported adverse events for methadone from a decade earlier. In contrast, the number of reported adverse events for all medicines in 2021 was 3 times the number of reported adverse events for all medicines from a decade earlier. This indicates that there was a clear spike in reported adverse events for methadone during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Still, there was no clear spike in reported adverse events for all medicines during the COVID-19 pandemic. This means that the increase in reported adverse events for methadone during the COVID-19 pandemic was unique to methadone, indicating that there is a high probability of external factors influencing the increase in usage of methadone. In 2013, the initial rise of reported methadone adverse events was suggestive of an opioid addiction crisis, seven years before the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to note that this rise in reported methadone adverse events occurred nearly 18 years after the approval of Oxycodone and 14 years after the first wave of the opioid epidemic. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the methadone adverse events spiked, suggestive of a sudden and troubling worsening of the third wave of the opioid epidemic.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

A strength of the FAERS system is that it allows public participation in adverse reporting, which aids in monitoring adverse events, as compared to adverse reporting being limited solely to health professionals. The system also enables the general public, doctors, and patients to access reports promptly. Additionally, as this study utilized anonymous information from the FAERS Public Dashboard, the data was free in the public domain, allowing for ethical research practices.

However, the FAERS Public Dashboard does have some limitations. The system may contain incomplete reports, inaccurate reports, or duplicate reports. As the data in this system relies on reported adverse events, some information can be inaccurate as adverse events may go completely unreported. Finally, the reporting of an adverse event associated with the use of a drug does not necessarily prove that the drug caused the event. Adverse events are often correlated with many external variables that may depend on environmental, patient-specific, or behavioral factors.

The data may not provide exact counts of methadone-related adverse events, but it provides a reliable estimate of trends in methadone adverse event reporting over time. A study utilizing the CDC’s Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) was used to examine methadone-treated overdoses during the pandemic [16]. Its results corroborate the results from the FAERS database, finding that there was a 48% increase in overdoses involving methadone between 2019 and 2020 [16]. So while the FAERS database may include duplicate or incomplete reports, the overall trends remain robust indicators of changes in reporting patterns over time. Relative to all medications, methadone’s reported adverse events increased disproportionately: whereas all medications collectively showed modest year-to-year increases, methadone’s reporting surged markedly in the identified periods. The present study still suggests that methadone adverse events showed concerning trends both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.2. Related Scholarly Works

There was an increase in the permitted amount of methadone take-home doses for the treatment of Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) by the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) at the start of the COVID-19 Pandemic [17]. A study of 183 patients at a single methadone clinic in Spokane, Washington, examined the impacts of this policy change and revealed that the mean number of methadone take-home doses increased from 11.4 take-home doses per 30 days to 22.3 take-home doses per 30 days after SAMHSA relaxed the rules on methadone prescriptions [17]. All individuals with OUD were given similar access to methadone take-home doses regardless of individual demographics, so an individual’s demographics did not influence their access to OUD treatment [17]. Another study conducted in 8 opioid treatment programs across the state of Connecticut, with an average of 837 individuals with OUD in each program, indicated similar results [18]. This suggests that the increase in the number of take-home doses was most likely not unique to Spokane, Washington, or any specific geographic area. There was a 16,700% increase in the percentage of patients receiving 28-day take-home doses [18]. Additionally, 75.2% of patients transitioned into telehealth, and there was an 84.1% decrease in in-person individual counseling; this indicates that there were many individuals who lost the added value of seeing their doctors in person, and some individuals who completely lost the guidance of their healthcare experts in treating OUD and managing their methadone dosages [18].

This increase in the ease of accessibility to methadone, coupled with the decrease in professional supervision, allows for the increased potential of misuse. Multiple treatment programs within the studied clinics stated that patients were experiencing difficulties due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and healthcare professionals expressed concerns about the new SAMHSA guidelines [18].

However, while the studies conducted in Washington and Connecticut found no negative impacts on the treatment of OUD associated with them, they agreed with this current study in that there was an increase in take-home dose prescriptions [17]. These studies report that the SAMHSA exemption and increase in take-home doses resulted in improved patient satisfaction [17]. However, the current study’s findings from the FAERS Dashboard indicate that there was a clear spike in methadone adverse event reporting in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic that was unique to methadone.

During a worldwide pandemic, infection control measures may cause many unintended consequences, such as an increase in access to synthetic opioids such as methadone due to the SAMHSA exemption. The study utilizing the CDC WONDER database had differing results from the studies conducted in Washington and Connecticut. It drew data from death certificates to determine methadone-related overdose trends [16]. Additional data from the Drug Enforcement Administration’s ARCOS database was used to examine accessibility and spread of methadone and treatment programs across all fifty states and Washington, DC [16]. The study accounts for three possible causes for the 48.1% increase in methadone overdoses between 2019 and 2020 [16]. The first was an accumulation of several policies: an increase in take-home dosages, reduced urine analysis, and decreased counseling sessions [16]. Another possibility was the increase in buprenorphine availability, through telemedicine, for new patients in comparison to methadone, which was prescribed in person. Methadone was better for retaining patients in OUD treatment, so in a time of economic and social distress, methadone was prescribed more often to those at a higher risk for overdose [16]. The final possibility was attributed to methadone’s long half-life, allowing it to stay in the bloodstream for longer times [16]. This means that even if other substances, such as xylazine or fentanyl analogues, contributed to the overdose, methadone is more likely to be detected in postmortem toxicology testing; thus, methadone is more likely to be the one listed on the death certificate [16].

Another study analyzed trends in methadone treatment dispensing among Medicare Advantage (MA) beneficiaries after two policy changes in 2020 relating to methadone access due to the pandemic [19]. Methadone was not covered for MA enrollees in 2019, so the dispensing rate in 2019 was 0 [19]. However, in 2020, after the policy change that covered methadone, methadone claims gradually increased from 0.98 per 1,000 enrollees in early 2020 to 4.71 per 1,000 in early 2022 [19]. The biggest increases were seen in beneficiaries under 65 and those eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid [19]. This indicates that the policy change increased dispensary rates and economic access to methadone as a medication for OUD during the economic uncertainty of the pandemic [19].

There are many potential reasons behind the increase in methadone adverse events and reports during the COVID-19 pandemic. With an increase in accessibility, there was also an increase in unsupervised prescriptions of methadone in the treatment of OUD due to control measures preventing individuals from meeting with doctors in person. It is important to note that a majority of individuals receiving OUD treatment fall within the 18-64 years age range, which was notably impacted most impacted by methadone. With a limited amount of supervision for individuals in possession of methadone, there were increased chances of misuse, which may account for the spike in adverse event reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic. This discrepancy in findings could be attributed to differences in study design and methodology, sample populations, or other factors not accounted for between the studies.

One possibility for future research within the range of methadone usage during the COVID-19 pandemic could include examining data sets with the number of prescriptions for methadone that were filled over this time. Another avenue for research includes analyzing the reported adverse events for other medicines used to treat addictions to other substances and OUD before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a deeper understanding of the opioid epidemic during this period overall. Finally, it would be interesting to examine the potential solutions to counteract the increasing misuse of opioids, such as methadone, during times when infectious diseases become more imminent. This could include events similar to the pandemic itself, but is not limited to widespread events, and can be later researched on smaller-scale events, such as in a local community.

Access to opioids, especially those like methadone that are used to treat OUD, posess a high risk for potential misuse when considering their addictive potential. It is critical to implement preventative measures to minimize the consequences of disruptions in opioid access.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the opioid epidemic is an imminent public health crisis, resulting in major negative impacts across the nation. Synthetic opioids such as methadone, along with a multitude of other treatments, have been implemented in an attempt to overcome opioid addiction. The findings of this study demonstrate a significant spike in adverse event reporting unique to methadone in comparison to all medications during the COVID-19 pandemic, based on data in the FAERS Database. This emphasizes the need for caution in OUD treatment practices and regulation, especially during times of disrupted healthcare access and increased risk of misuse, such as the global pandemic.

The observed increase in methadone adverse events during the COVID-19 pandemic may be driven by several factors. Relaxed take-home policies, while improving access, likely led to more unsupervised use and potential diversion. Reduced in-person clinical monitoring, heightened stress and social isolation, and variability in policy implementation across states may have further amplified risks. To mitigate these challenges in future health emergencies, policymakers should implement tiered take-home regulations that balance accessibility with patient safety, ensuring consistent application across jurisdictions. Surveillance systems should integrate real-time dispensing and adverse event data, stratified by age, sex, and comorbidities, to identify high-risk populations promptly. Clinically, providers should employ risk assessment tools to guide take-home dosing, supplement in-person care with robust telehealth counseling, and educate patients on safe dosing and storage practices. These measures collectively aim to preserve access to life-saving methadone treatment while minimizing potential harm during periods of healthcare disruption.

Despite the uncertainty in the singular cause of this spike, it is important to acknowledge that the increase in methadone adverse events was augmented by the development of multiple social, economic, and policy-related factors during the pandemic, as well as the unique properties of methadone itself. Future research could potentially explore how similar disruptions in access to opioids may influence adverse event reporting and OUD treatment, and research should determine if the suggested policies and surveillance methods are effective ways to minimize the impact of these disruptions.

References

[1] R. Adlaka, R. Benyamin, R. Buenaventura, S. Datta, S. E. Glaser, N. Sehgal, A. M. Trescott, and R. Vallejo, "Opioid Complications and Side Effects," Pain Physician, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 105-120, 2008 [Online]. Available: https://painphysicianjournal.com/current/pdf?article=OTg1&journal=42. Available: View Article

[2] T. Che and B. L. Roth, "Molecular basis of opioid receptor signaling," Cell, vol. 186, no. 24, pp. 5203-5219, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.10.029. Available: View Article

[3] U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Understanding the opioid overdose epidemic | overdose prevention," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nov. 1, 2024. [Online]. Available: View Article

[4] U.S. Federal Communications Commission, "Focus on opioids," Connect2Health FCC, 2024. [Online]. Available: View Article

[5] E. A. Shipton, E. E. Shipton, and A. J. Shipton, "A review of the opioid epidemic: What do we do about it?" Pain and Therapy, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 23-26, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-018-0096-7. Available: View Article

[6] U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse, "Opioids," National Institute on Drug Abuse, Nov. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: View Article

[7] U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. "Drug Fact Sheet: Morphine." DEA.gov, U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, April 2020, Available: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/Morphine-2020.pdf. Available: View Article

[8] U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. "Drug Fact Sheet: Oxycodone." DEA.gov, U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, April 2020, https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/Oxycodone-2020_0.pdf Available: View Article

[9] U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse. "Commonly Used Drug Charts." National Institute on Drug Abuse, 19 September 2023, Accessible: https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/commonly-used-drugs-charts#heroin. Available: View Article

[10] U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. "Drug Fact Sheet: Fentanyl." DEA.gov, U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, October 2022, Accessible: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2023-06/Fentanyl%202022%20Drug%20Fact%20Sheet-update.pdf. Available: View Article

[11] Gill, James R., et al. "Reliability of postmortem fentanyl concentrations in determining the cause of death." Journal of Medical Toxicology, vol. 9, no. 1, 2012, pp. 34-41. PubMed, Accessible: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22890811/. Available: View Article

[12] E. N. Aroke, G. Lai, S.J. Zhang, "Rediscovery of methadone to improve outcomes in pain management," Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 425-434, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2021.08.011. Available: View Article

[13] Bourgois, Philippe, et al. "Every 'never' I ever said came true": transitions from opioid pills to heroin injecting." International Journal of Drug Policy, vol. 25, no. 2, 2014, pp. 257-266. PubMed, Available; https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24238956/. Available: View Article

[14] Zee, Art Van. "The Promotion and Marketing of OxyContin: Commercial Triumph, Public Health Tragedy." Am J Public Health, vol. 99, no. 2, 2009, pp. 221-227. PubMed, Accessible: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2622774/?. Available: View Article

[15] T. P. George and T. R. Kosten, "The neurobiology of opioid dependence: Implications for treatment," Science & Practice Perspectives, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 13-20, 2002. [Online]. Available: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2851054/. Available: View Article

[16] D. E. Kaufman, A. L. Kennalley, K. L. McCall, B. J. Piper, "Examination of methadone involved overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic," Forensic Science International, vol. 334, Article 111579, March, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2023.111579. Available: View Article

[17] S. Amiri, O. Amram, P. J. Joudrey, R. Lutz, V. Panwala, and E. Socias, "The impact of relaxation of methadone take-home protocols on treatment outcomes in the COVID-19 era," The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 722-729, Oct. 20, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2021.1979991. Available: View Article

[18] S. Brothers, R. Heimer, and A. Viera, "Changes in methadone program practices and fatal methadone overdose rates in Connecticut during COVID-19," Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, vol. 131, p. 108449, Dec. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108449. Available: View Article

[19] E. A Taylor, J. H. Cantor, and A. C. Bradford, K. Simon, B. D. Stein, "Trends in Methadone Dispensing for Opioid Use Disorder After Medicare Payment Policy Changes," Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open, vol. 6, no. 5, Article e2314328, May 2023, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.14328 Available: View Article